The Eternal Return:

Genesis and Interpretation*

By Paul D'Iorio

1. Return of the Same?

Gilles Deleuze claims that "we misinterpret the expression 'eternal return' if we understand it as 'return of the same'," above all, he says, we must avoid "believing that it refers to a cycle, to a return of the Same, a return to the same," and further, he contends that "It is not the same which returns, it is not the similar which returns; rather, the Same is the returning of that which returns,-in other words, of the Different; the similar is the returning of that which returns,-in other words of the dissimilar. The repetition in the eternal return is the same, but the same in so far as it is said uniquely of difference and the different."[1] This interpretation, which was widespread in France and in the world, relies on one fragment by Nietzsche, and one fragment only. This fragment was published as "aphorism" 334 of Book Two of the non-book known as The Will to Power.[2]

It is worth mentioning that this so-called aphorism was put

together by the editors of The Will to Power, who merged two posthumous

fragments from 1881 in which Nietzsche compared his own conception of the eternal

return of the same as a cycle taking place within time with Johannes Gustav

Vogt's mechanistic conception, which involved (besides the eternal return in

time) the eternal co-existence of the same in space. This dialogue between

Nietzsche and Vogt is clearly visible in the manuscript not only because the

author refers explicitly to Vogt's most important work (Force: A Realistic

and Monistic Worldview) just before these two posthumous fragments as well

as between them; but also because the text itself quotes some concepts and

refers to some technical terms taken from Vogt's book in quotation marks, such

as "energy of contraction."[3] Vogt declared that the world is made of one single and absolutely homogenous

substance which is spatially and temporally defined, immaterial and

indestructible, and which he called "force" (Kraft) and whose

"fundamental mechanistic, unique and immutable force of action is contraction."[4] After reading this passage and highlighting some others in the margin of his

copy of Vogt's book, Nietzsche takes his notebook M III 1 and writes

the fragment quoted by Deleuze:

Supposing that there were indeed an "energy of contraction" constant in all centers of force of the universe, it remains to be explained where any difference would ever originate. It would be necessary for the whole to dissolve into an infinite number of perfectly identical existential rings and spheres, and we would therefore behold innumerable and perfectly identical worlds COEXISTING [Nietzsche underlines this word twice] alongside each other. Is it necessary for me to admit this? Is it necessary to posit an eternal coexistence on top of the eternal succession of identical worlds.[5]

In the French version of the Will to Power used by

Deleuze, the term "Contractionsenergie" is translated as "concentration

energy" instead of "contraction energy," and the phrase "Ist dies nöthig für

mich, anzunehmen?" is translated as "is it necessary to admit this" instead

of "is it necessary for me to admit this?" and this does away with the whole

meaning of the comparison. The effects of arbitrary cuts, of the distortion of

the chronological order, of the oversights and approximations of the French

translation of The Will to Power combined lead to the

obliteration of the dialogue between Nietzsche and Vogt and it looks as if

Nietzsche were criticizing his own idea of the eternal return of the

same as a cycle in this note scribbled in his notebook-which would make it an

exception in his whole written work. Deleuze, whose entire interpretation

relies on this sole posthumous note whilst ignoring all the others, comments:

"The cyclical hypothesis, so heavily criticized by Nietzsche (VP II 325 and

334), arises in this way."[6] In fact, Nietzsche was not criticizing the cyclical hypothesis but

only the particular form of that hypothesis presented in Vogt's work. All of

Nietzsche's texts without exception speak of the eternal return as the

repetition of the same events within a cycle which repeats itself eternally.[7]

If Deleuze's interpretation holds that the eternal return is

not a circle, then what is it? A wheel moving centrifugally, operating a "creative

selection," "Nietzsche's secret is that the eternal return is selective" says Deleuze:

The eternal return produces becoming-active. It is

sufficient to relate the will to nothingness to the eternal return in order to

realize that reactive forces do not return. However far they go, however deep

the becoming-reactive of forces, reactive forces will not return. The small,

petty, reactive man will not return.

Affirmation alone returns, this that can be affirmed alone

returns, joy alone returns. Everything that can be denied, everything that is

negation, is expelled due to the very movement of the eternal return. We were

entitled to dread that the combinations of nihilism and reactivity would

eternally return too. The eternal return must be compared to a wheel; yet, the

movement of the wheel is endowed with centrifugal powers that drive away the

entire negative. Because Being imposes itself on becoming, it expels from

itself everything that contradicts affirmation, all forms of nihilism and

reactivity: bad conscience, ressentiment..., we shall witness them only

once. [...] The eternal return is the Repetition, but the Repetition that

selects, the Repetition that saves. Here is the marvelous secret of a selective

and liberating repetition.[8]

There is no need to remind the reader that neither the image

of a centrifugal movement nor the concept of a negativity-rejecting repetition

appears anywhere in Nietzsche's writings, and indeed Deleuze does not refer to

any text in support of this interpretation. Further, one could highlight that

Nietzsche never formulates the opposition between active and reactive forces,

which constitutes the broader framework of Deleuze's interpretation. For some

years, Marco Brusotti has called attention to the fact that Deleuze introduced a

dualism that does not exist in Nietzsche's writings. To be sure, the German

philosopher describes a certain number of "reactive" phenomena (for example, in

the second essay of the Genealogy of Morality, § 11, he talks about

"reactive affects" [reaktive Affekte], "reactive feelings" [reaktive Gefühlen], reactive men [reaktive Menschen]); but these are nonetheless the result of

complex ensembles of configurations of centers of forces that remain in

themselves active. Neither the word nor the concept of "reactive forces"

ever appears in Nietzsche's philosophy.[9]

We would like to pause for one moment to cast a

philosophical glance on Deleuze's interpretation as a whole.[10] In his portrayal of Nietzsche, Deleuze elaborates an extraordinary philosophy

of affirmation and joy, which clears existence of all reactive, negative and

petty elements. He strives to locate a mechanism that-unlike the negation of

negation, which characterizes Hegel's (and Marx's) dialectic-would produce the

"affirmation of affirmation" in the eternal return: :

The eternal return is this highest power, a synthesis of affirmation which finds its principle in the Will. The lightness of that which affirms against the weight of the negative; the games of the will to power against the labor of the dialectic; the affirmation of affirmation against that famous negation of the negation.[11]

Deleuze opposes the historical course of the Hegelian notion

that confronts, struggles and finally dialectizes the negative and results in a

consoling teleology leading to the triumph of the idea or the liberation of the

masses with the centrifugal movement of the wheel, which simply ejects the

negative. It is still a case of a consoling and optimistic teleology, which,

instead of confronting the weight of history, the grief and the negative, makes

it disappear in one centrifugal stroke of a magic wand. There is reason to

worry that this be a case of repression, which, unable to dialectize or accept

the negative, simply seeks to exorcise it in one gesture of "creative selection."

But exorcism is a feat of magic and not of philosophy: it is unfortunately not

enough to make the negative disappear. In all probability, the negative will

come back with a vengeance.

In contrast to Deleuze's "affirmation of affirmation", which

affirms only affirmation, Nietzsche conceives of the eternal return from a

rigorously non-teleological perspective as the accomplishment of a philosophy

strong enough to accept existence in all its aspects, even the most negative,

without any need to dialecticize them, without any need to exclude them by way

of some centrifugal movement of repression. It denies nothing and incarnates

itself in a figure similar to the one Nietzsche, in Twilight of the Idols,

draws of Goethe:

Such a spirit, who has become free stands in the middle of the world with a cheerful and trusting fatalism in the belief that only the individual is reprehensible, that everything is redeemed and affirmed in the whole-he does not negate anymore. Such a faith however, is the highest of all possible faiths: I have baptized it with the name of Dionysus.[12]

2. Zarathustra, the Master of the Eternal Return

All of Nietzsche's arguments for a detailed theoretical

explanation of the eternal return are contained in a notebook written in

Sils-Maria during the summer of 1881. In the published work, the content of the

doctrine remains unchanged but it is presented by Zarathustra according to very

different strategies and philosophical forms of argumentation. We will start

analysing the public presentation of the eternal return before discussiong

theoretical arguments in the third part of this article.

In the dramatic and dialogical structure of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, one needs to pay attention to the rhetorical progression

that takes place between the moments where the thought of the eternal return is

enunciated. Even more, we must pay attention to which characters announce the

doctrine or which ones they announce it to. Nietzsche carefully stages

Zarathustra's maturation process, his gradual assimilation of the eternal

return and the effects that the doctrine has on the different human types to

whom it is intended. Indeed, this is where lies the originality (and the force)

of Zarathustra's style over forms like the treatise or the traditional

philosophical essay. While reading Nietzsche's aphoristic works-and even more

so the manuscripts-one must pay attention to the dialogue that Nietzsche, in

the wake of his readings, establishes with his philosophical interlocutors.

While reading Zarathustra, one must in the same way pay continuous

attention to the narrative context, to the role played by some characters and

to the nuances a word adopts when enunciated by or to different characters.

Hence the double question which we must bear in mind throughout our analysis of

the role of the eternal return in Zarathustra: who speaks? who listens?

2.1 Speaking Hunchback-ese to the Hunchbacks

Zarathustra being "the master of eternal return," this

doctrine pervades all four parts of the work. In certain passages, it is mentioned

in an especially explicit fashion. I have chosen five such passages, which I

would like to discuss briefly.[13]

The first passage dealing with the eternal return, even

though Zarathustra is unable to mention it directly, is the chapter "On

Redemption" from part two of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. There, Nietzsche

opposes two conceptions of temporality and of redemption. On the one hand, the

redemption which regards the transitory character of becoming as the

demonstration of its original sin and valuelessness and seeks to liberate

itself from timeliness in order to rejoin the immutable essence. On the

other hand a conception of redemption through time that Zarathustra

begins to lay out when he speaks of the will that wills "backwards" (Zurückwollen).

Several intertextual keys point to Schopenhauer as the representative of the

first, nihilistic redemption embedded in a spirit of revenge against time. Schopenhauer

wrote that:

In time each moment is, only in so far as it has effaced its father the preceding moment, to be again effaced just as quickly itself. Past and future (apart from the consequences of their content) are as empty and unreal as any dream; but present is only the boundary between the two, having neither extension nor duration.

Zarathustra however calls "mad" this Oedipal conception of temporality:

Everything passes away, therefore everything deserves to pass away! 'And this is itself justice, that law of time that time must devour its children': thus did madness preach.

Schopenhauer spoke of the existence of an eternal justice and of the necessity to deny the will to live:

The world itself is

the tribunal of the world. If we could lay all the misery of the world in one

pan of the scales, and all its guilt in the other, the pointer would certainly

show them to be in equilibrium.

After our observations

have finally brought us to the point where we have before our eyes in perfect

saintliness the denial and surrender of all willing, and thus a deliverance

from a world whose whole existence presented itself to us as suffering, this

now appears to us as a transition into empty nothingness.[14]

Zarathustra replies:

o deed can be annihilated: so how could it be undone through punishment! This, this is what is eternal in the punishment 'existence': that existence itself must eternally be deed and guilt again! 'Unless the will should at last redeem itself and willing should become not-willing-': but you know, my brothers, this fable-song of madness!

Yet, this chapter does not focus solely on Schopenhauer but addresses an entire philosophical tradition that goes back to Anaximander, at least.[15] The first pages of the second Untimely Meditation bear the mark of such a tradition; there, the young Nietzsche speaks of the weight of the "Es war," the "it has been" which Zarathustra now intends to redeem through the active acceptance of the past. But even as his discourse now seems to lead him to enunciate the doctrine of eternal return, Zarathustra brutally interrupts himself:

'Has the will yet become its own redeemer and joy-bringer? Has it unlearned the spirit of revenge and all gnashing of teeth? 'And who has taught it reconciliation with time, and something higher than any reconciliation? 'Something higher than any reconciliation the will that is will to power must will-yet how shall this happen? Who has yet taught it to will backwards and want back as well?' -But at this point in his speech it happened that Zarathustra suddenly fell silent and looked like one who is horrified in the extreme.

Zarathustra fails to enunciate or even to name eternal return. And the hunchback (representing the scholar burdened by the weight of history and of his erudition) listened to him while covering his face with his hands because he already knew what Zarathustra was getting at. He responds: why didn't you say it? "But why does Zarathustra address us in a different fashion than he addresses his disciples?" And Zarathustra, regaining his good spirits after a moment's hesitation, replies: "But what is the surprise in this, with hunchbacks, surely, one must speak hunchback-ese." Still, the hunchback is well aware of the fact that Zarathustra not only lacks the strength to announce his doctrine to others, but even more, that he does not even manage to confide in himself:

'Good,' said the hunchback. 'And with students one may well tell tales out of school. 'But why does Zarathustra speak otherwise to his students-than to himself?-'

2.2 The Shepherd of Nihilism

After the chapter "On Redemption," where Zarathustra dares not expose his doctrine, the eternal return begins to be enunciated in part three of the work. In the first place, it is the dwarf who formulates it in the chapter "On the Vision and the Riddle." Facing the "gate of the instant" which symbolizes the two infinities that stretch towards the past and the future, the dwarf whispers: "all truth is crooked, time itself is a circle." The dwarf represents the spirit of gravity, and he embodies the herd morality, "the belittling virtue" which is the title of another chapter from part III. The dwarf can endure the eternal return without great difficulties because he has no aspirations; unlike Zarathustra he does not wish to climb the mountains that symbolize elevation and solitude. In two unpublished notes, from the summer and the fall of 1883, Nietzsche writes:

The doctrine is at first favored by the rabble, before it gets to the superior

men.

The doctrine of recurrence will first smile to the rabble,

which is cold and without any strong internal need. It is the most ordinary of

life instincts, which gives its agreement first.[16]

Hence, the content of the doctrine is the same, but whereas

the dwarf can endure it (because he interprets it according to the pessimistic

tradition for which "nothing is new under the sun"), Zarathustra, who is the

"advocate of life" regards the eternal return as the strongest objection to

existence, and as the rest of the dream suggests, he does not yet succeed in

accepting it.[17] After the vision at the gate of the instant, the chapter is brought to an end

by the enigma of the shepherd. Under the most desolate moonlight, in the midst

of wild cliffs, Zarathustra glimpses at a shepherd who has a black serpent

dangling from his mouth. The serpent represents nihilism, which accompanies the

thought of eternal return, the condition by which one's throat is filled with

all things most difficult to accept, all things darkest. Zarathustra, who

cannot tear the serpent away from the throat of the shepherd, cries to him:

"bite, bite!" The shepherd bites, spits the serpent's head into the distance,

and, as if transformed, starts to laugh.

This is the anticipation and the premonition of what

Zarathustra himself will have to confront, and which will still take him years

and years. Only towards the end of part III are we told, in the chapter titled

"The Convalescent," that he succeeded at last, even though he paid for it with

eight days of illness. In that chapter, the eternal return is enunciated anew,

this time by Zarathustra's animals, whereas Zarathustra himself is still

lacking the strength to speak.

Deleuze has correctly identified the rhetorical progression

between the different formulations of eternal return at work in Thus Spoke

Zarathustra. Only, he interprets those differences as the expression of a

shift in the content of the doctrine: as if Zarathustra was gradually realizing

that the eternal return is in fact not a circle that repeats the same, but a

selective movement which eliminates the negative.

If Zarathustra recovers, it is because he understands that the eternal return is not this. He finally understands the unequal and the selection contained in the eternal return. Indeed, the unequal, the different, is the true reason of the eternal return. It is because nothing is equal, nor is anything the same, that 'it' recurs (Deleuze, "Conclusions - sur la volonté de puissance et l'éternel retour" (1967): 284).

Actually, if it is not Zarathustra who formulates his own doctrine, it is because he lacks the strength to teach it, even though he succeeds in evoking the thought of eternal return, using it as a weapon, and finally, in accepting it when he finally cuts off the serpent's head himself. As a result, the animals dutifully remind him of his doctrine, the one he must teach:

For your animals know this well, O Zarathustra, who you

are and who you are to become: behold-you are the teacher of the eternal

return-that is now your fate [...]

Behold, we two know what you teach: that all things

recur eternally and we ourselves with them and that we have already been here

an eternity of times, and all things with us.

You teach that there is a Great Year of Becoming, a

monster of a Great Year, which lust, like an hourglass, turn itself over anew

again and again, that it may run down and run out ever new-

-such that all these years are the same, in the greatest

and smallest respects-such that we ourselves are in each Great Year the same as

ourselves, in the greatest and smallest respects. [...] I come again with

this sun, with this Earth, with this eagle, with the serpent,-not to a

new life, or a better life or a similar life:-I come eternally again to this

self-same life, in the greatest and smallest respects, so that again I teach

the eternal return of all things."

Like the dwarf, and even more than him, the animals are not afraid of this doctrine for a simple reason: they are totally deprived of any historical sense. In the beginning of his second Untimely Meditation, "On the Uses and Disadvantages of Historical Studies for Life" Nietzsche had opposed the human with the animal. The animal is tied to the post of the instant, while the human is bound up and chained to the past and the weight of history. In the preparatory notes to this first section of the second Untimely, Nietzsche explicates the literary reference, which he conceals later, in the final text. The reference is to Giacomo Leopardi's Night Song of a Wandering Shepherd in Asia.[18] As a pessimistic poet, whom both Schopenhauer and Nietzsche were very fond of, Leopardi had represented human life as the life of a shepherd who, while in the desert at night, speaks to the moon about the valuelessness of all things human.

My flock, you lie at

ease, and you are happy,

Because you do not

know your wretchedness!

How much I envy

you!

Not just because

you go

Almost without

distress,

And very soon

forget

All pains, all

harm, and even utmost terror;

But more because

you never suffer boredom

These are the verses quoted by Nietzsche in his notebook,

and which he paraphrases in the final text. It is the same shepherd we

encounter again in Zarathustra's dream, the shepherd of pessimism and nihilism

(the poem's ending is "Whether in lair or cradle, / It may well be it always is

upon / A day of great ill-omen we are born"), the shepherd whose mouth nihilism

has choked and who must find the strength to spit it out.[19]

However, Zarathustra, who is the advocate of life, has

understood that by having the strength to accept the eternal return, it is

possible to fight pessimism. The rhetorical progression in the formulation of

the eternal return does not signify that Zarathustra encounters different

doctrines, but faces us with different ways to apprehend the doctrine of the

eternal return, each one corresponding to different degrees of the historical

sense. All of this becomes clearer in the rest of the formulations of the

eternal return (which Deleuze ignores like many others).[20]

2.3 The Game of "Who to Whom"

Shortly after the chapter devoted to the convalescent, we find "The Other Dance-Song." There develops a parodic game based upon a little intertextual hint. Life says to Zarathustra:

O Zarathustra! Please, don't you crack your whip so terribly! For well you know: noise murders thoughts,-and just now such tender thoughts are coming to me!

This suffices to evoke the figure of Schopenhauer, the archenemy of noise, who had represented the dreadful condition of the philosopher in the midst of the urban bustle, in this passage from Parerga and Paralipomena:

I have to denounce as the most inexcusable and scandalous noise the truly infernal cracking of whips in the narrow resounding streets of towns; for it robs life of all peace and pensiveness. [...] With all due respect to the most sacred doctrine of utility, I really do not see why a fellow, fetching a chart-load of sand or manure, should thereby acquire the privilege of nipping in the bud every idea that successively arises in ten thousand heads (in the course of half an hour's journey through a town). Hammering, the barking of dogs, and the screaming of children are terrible, but the real murderer of ideas is only the crack of a whip.[21]

As regards the possibility of starting a new life,

Schopenhauer wrote: "But perhaps at the end of his life, no man, if he be

sincere and at the same time in possession of his faculties, will ever wish to

go through it again. Rather than this, he will much prefer to choose complete

non-existence" and: "If we knocked on the graves and asked the dead whether

they would like to rise again, they would shake their heads."[22]

Eduard von Hartmann, Schopenhauer's pet monkey, drew an image quite typical of

his philosophy from this passage. There, death asked a man from the average

bourgeoisie of the time whether he would accept to live his life over again.

Let's imagine a man who is not a genius, who hasn't

received any more than the general education of any modern man; which possesses

all advantages of an enviable position, and finds themselves in the prime of

life. A man with a full awareness of the advantages he enjoys, when compared to

the lower members of society, to the savage nations and to the men of the

Barbarian ages; a man who does not envy those above him, and who knows that

their lives are plagued with inconveniences which he is spared; a man, finally,

who is not exhausted, not blasé with joy, and not repressed by any exceptional

personal misfortunes.

Let us suppose that death come and find this man and

addresses him in these terms: "the span of your life is expired, the time has

come when you must become the prey of nothingness. Yet, it is up to you to

choose if you wish to start again-in the same conditions, with full forgetting

of the past-your life that is now over. Now chose!"

I doubt that our man would prefer to start again the

preceding life-play rather than enter nothingness (Eduard von Hartmann, Philosophie

des Unbewussten. Versuch einer Weltanschauung (Berlin: Carl Duncker's

Verlag, 1869): 534).

Nietzsche himself took over this image in his first public formulation of the doctrine of the eternal return from the famous aphorism 341 of the Gay Science. This time it is a demon that, having accessed the most remote of all solitudes, asked man whether he would live his life again, just as it was. In "The Other Dance-Song," Nietzsche plays at parodying Schopenhauer, Hartmann, and himself as this time it is not life, death, or a demon that brandish the eternal return as a dreadful scare-crow before the fortunate men, it is Zarathustra, desperate and on the brink of suicide, who announces the doctrine of eternal return to life. And he whispers it softly to her ears, through her beautiful blonde curls:

Thereupon, Life looked pensively behind her and about her

and said softly: "O Zarathustra, you are not true enough to me!

You have long not

loved me as much as you say you do; I know you are thinking that you want to

leave me soon.

There is an

ancient heavy heavy booming-bell: at night its booming comes all the way up to

your cave:-

-and when you hear

this bell at midnight strike the hour, between the strokes of one and twelve

you think-

-you think then, O Zarathustra, well I know, of

how you wish to leave me soon!-

"Yes," I answered

hesitantly, but you also know that-" And I said something into her ear right

through her tangled yellow crazy locks of hair.

"You know that, O Zarathustra? No one knows

that.- -"

The first time that Zarathustra announces his doctrine, he addresses life itself. At that very moment, the midnight bells start ringing, while Zarathustra dances around:

One!

O man! Take care!

Two!

What does deep

midnight now declare?

Three!

I sleep, I sleep-

Four!

From deepest dream

I rise for air

Five!

The world is deep

Six!

Deeper than any

day has been aware

Seven!

Deep is its woe

Eight!

Joy-deeper still

than misery:

Nine!

Woe says: now go!

Ten!

Yet all joy wants

eternity

Eleven!

-Wants deepest,

deep eternity

Twelve!

But what does this circular midnight song signify, held in this way between suicide and the dialogue with life? This question is elucidated by the last mention of the eternal return, in the last chapters of the fourth Zarathustra.

2.4 The Ugliest Man and the Most Beautiful Moment

The ugliest man, one of the superior men to whom the fourth

part of Zarathustra is devoted, is the personification of historical

sense. Consequently he is God's murderer and therefore, he understands how

terrible history is and how unbearable the repetition of this series of

meaningless massacres and vain hopes is.[23] The highest degree of historical sense implies the greatest difficulty in

accepting the eternal return and this is precisely the task that Nietzsche

appoints to the "feeling of humanity" in the superb aphorism 337 of the Gay

Science:

The "humaneness" of the future. [...] Anyone who manages to experience the history of humanity as a whole as his own history will feel in an enormously generalized way all the grief of an invalid who thinks of health, of an old man who thinks of the dreams of his youth, of a lover deprived of his beloved, of the martyr whose ideal is perishing, of the hero on the evening after the battle who had decided nothing but brought him wounds and the loss of his friends. But if one endured, if one could endure this immense sum of grief of all kinds while yet being the hero who, as the second day of battle breaks, welcomes the dawn and its fortune, being a person whose horizon encompasses thousands of years past and future, being then heir of all the nobility of all past spirit-an heir with a sense of obligation, the most aristocratic of all nobles and at the same time the first of a new nobility-the like of which no age has yet seen or dreamed of; if one could burden one's soul with all of this-the oldest, the newest, losses, hopes, conquests, and the victories of humanity; if one could finally contain all this in one soul and crowd it into a single feeling-this would surely have to result in a happiness that humanity has not known so far: the happiness of a god full of power and love, full of tears and laughter, a happiness that, like the sun in the evening, continually bestows its inexhaustible riches, pouring them into the sea, feeling richest, as the sun does only when even the poorest fisherman is still rowing with golden oars! This godlike feeling would then be called-humaneness.[24]

Overhumanity, Zarathustra exclaims. "I am all the names in history," Nietzsche declares at the end of his conscious life, absorbed in the exaltation that shall lead him towards folly. Accordingly, the ugliest man (it is now his time to announce the doctrine) informs the superior men that "earthly life is worth living," in the second-to-last chapter of part IV: "One day, a feast in the company of Zarathustra was enough to teach me to love the earth. 'Is this life!' I shall tell death, 'well, once more!'" At this point, the old bell started sounding the hours at midnight, "the old midnight bell which had counted the heartbeats, the painbeats of your fathers" is another image that Nietzsche intends to be combining nihilism and all the woes of existence, and to whom Zarathustra opposes this reasoning, transforming and re-producing the Faustian sense of the instant:

Did you ever say yes

to a single joy? O my friends, then you said yes to all woe as well! All things are chained together, entwined, in

love.

-If you ever

wanted one time a second time, if you ever said 'you please me, Happiness!

Quick! Moment!' then you wanted it all back!

-All anew, all eternally,

all chained together, entwined, in love, oh! Then you loved the world-

-you the eternal

ones, love it eternally and for all time, and even to woe you say: "be gone,

but come back,!" for

all joy wants-eternity!

The eternal return is the most radical response possible to

theologies both philosophic and scientific, as well as to the linear

temporality of the Christian tradition: in the cosmos of eternal return, there

is no room for creation, providence or redemption. One is unable to either stop

time or direct it: every instant flows away, but it is fated to return,

identical, for better or for worse. Who, then, may have wished to live

again the same life? Who is it that would relish in taking the arrow away from

Chronos' hands and slipping the ring on the finger of eternity? Goethe looked

for an instant that he could urge thus: "stop here, you are beautiful."

Nietzsche, on his part, awaits a man who could declare to every instant:

"pass away and return, identical, in all eternity!" This man is the overhuman,

he is not an esthete, an athlete, or a product of some Aryan, slightly Nazi

eugenics. He is he who can say 'yes' to the eternal return of the same on

earth, while taking up the weight of history and keeping the strength to shape

the future.

The notebooks indicate that this very reasoning applied to

the individual Nietzsche, who had scribbled in the midst of his Zarathustrian

fragments: "I do not want my life to start again. How did I manage to

bear it? By creating. What is it that allows me to bear its sight? Beholding

the overman who affirms life. I have attempted to affirm it myself -Alas." And shortly after, on another page, he replied to his own question

thus: "The instant in which I created the return is immortal, it is for the

sake of that instant that I endure the return."[25] Nietzsche, the man of knowledge had attained the climax of his life at the very

instant in which he had grasped the knowledge he regarded as the most important

of all. When, at the end of his life, he became aware of having attained this

summit, he ceased to need an alter ego in order to affirm the life that forever

returns and as a conclusion to the Twilight of the Idols, which are the

very last lines published in his lifetime, he let these words be printed: "I,

the last disciple of the philosopher Dionysus,-I the master of the eternal

return."

3. Genesis, Inter-Textuality and Parody

Let us therefore return to this instant in which the philosopher is seized by his abysmal thought. In Ecce Homo, Nietzsche himself recalls the date and the birthplace of the Zarathustra, born out of the thought of the eternal return:

>I shall now tell the story of Zarathustra. The basic conception of the work, the idea of the eternal return, the highest formula of affirmation that can possibly be attained-belongs to the August of the year 1881: it was jotted down on a piece of paper with the inscription: '6,000 feet beyond man and time'. I was that day walking through the woods beside the lake of Silvaplana; I stopped beside a mighty pyramidal block of stone which reared itself up not far from Surlei. Then this idea came to me. (Ecce Homo, "Thus Spoke Zarathustra," §1)

This rendering seems to characterize the thought of eternal return as ecstatic hallucination, as inspired knowledge, as myth. Moreover, as we said, nowhere in his published works does one find any theoretical exposition of a doctrine that Nietzsche considered to be the apex of his philosophy, and which exerted in his mind a profound turmoil in the summer of 1881:

Thoughts rose against my horizon, thoughts the likes of which I have never seen before-I do not wish to reveal anything about them, and maintain myself in an unshakeable calmness. [...] The intensity of my feelings makes me laugh and shiver at once-it happened already a number of times that I couldn't leave my room for the laughable cause that my eyes were inflamed-for what reason? Everytime I had in my walks of the day before, cried too much, and not sentimental tears, but tears of excitement, singing and raving, full of a new view which is my privilege above all the men of this time (Letter to Peter Gast, August 14th, 1881).

It is therefore not surprising that a large part of the

Nietzsche scholarship has seen the eternal return as a myth, an hallucination,

in any case as a paradoxical and contradictory theory, a construct of classical

influences and reminisces of scientific doctrines wrongly understood. However,

the critical edition by Colli and Montinari leads us to question everything

again on this point as well as many others, and to leave behind the

hermeneutical and philosophical enthusiasms in order to focus on more modest

exercises in reading Nietzsche's text. Just like thoughts never surge from

nothing, this text is not without context. The page inscribed with the thought of

the eternal return is known to the scholarship, and has been abundantly quoted

and even reproduced in facsimle. However, the notebook containing that page is

largely ignored. This notebook does not register the stroke of lightning of an

ecstatic revelation. Instead, it contains a series of rational arguments in

support of the hypothesis of the eternal return.

M III 1-such is the reference number of this

in-octavo notebook kept in Weimar's Goethe-Schiller archives-is made up of 160

pages, carefully covered in about 350 fragments belonging (except for a few

rare exceptions) to the period from the spring to the fall of 1881. It is a

secret notebook. Nietzsche did not use its content in any of the published

works (it contains only the preparatory versions of a few aphorisms of the Gay

Science and two of Beyond Good and Evil). The reason is that

Nietzsche intended to use its contents for a scientific exposition of the

thought of the eternal return.[26] Given the fact that the arguments in support of the eternal return in the

notebooks of the subsequent years all pertain to those first reflexions, we are

faced with one of the rare cases in which Nietzsche's thoughts on a precise

issue do not undergo any modifications.[27]

Yet, this notebook, however important and unused in the

published works, fell victim to a series of editorial misfortunes and remained

unpublished until 1973, when it was published integrally and in a

chronologically reliable shape, while the editions anterior to Colli and

Montinari's "do not allow one to form an opinion, however approximate, of this

notebook and its specific character."[28] Before 1973, it was therefore near impossible, even for the most

philosophically and critically perceptive readers, to understand exactly the

theoretical formulation and organic links which unify this "posthumous thought"

to the rest of Nietzsche's work. Only the chronological arrangement of the

posthumous material offered by Colli and Montinari allows us to follow step by

step the relations between the occurrence of the hypothesis of the eternal

return, the attempts at a rational demonstration attached to it, and the other

lines of thought developed in the same period.[29]

3.1 Let us refrain from saying...

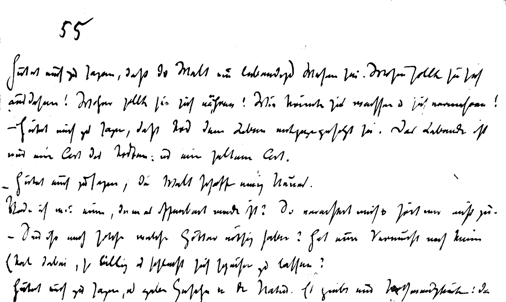

Let us open this notebook then, and instead of contemplating the first sketch of the eternal return on page 53, let us read what Nietzsche wrote in the very next page:

Figure 1: Notebook M III 1 of summer 1881, p. 49 (55 according to Nietzsche's numbering). Weimar, Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv.

Refrain from saying [Hütet

euch zu sagen] that the world is

a living being. In what direction would it expand! Where would it draw its

substance! How could it increase and grow!

-Refrain from

saying that death is what is opposed to life. The living is but a variety of

what is dead, and a rare one at that.

-Refrain from

saying that the world continuously creates something new.

Do I speak like a

man under the spell of a revelation? Then just keep from listening and treat me

with scorn.

-Are you of the

kind who still need gods? Doesn't your reason feel disgust at letting itself be

fed in such a gratuitous and mediocre way?

Refrain from saying

that there exists laws in nature. There are only

necessities, and therefore there is no one to command, no one who

transgresses."[30]

Apparently, it is a matter of a polemic against those who

considered the world as a living being, unfolding through a recursive structure

of speech: "Let you beware [Hütet

euch zu sagen] ..." What does that

mean? Why does Nietzsche turn against those who thought that the world is a

living thing, and who is this warning sent to? And why is Nietzsche using such

a rhetorical structure? And above all, what does it all have to do with the

doctrine of eternal return?

In order to address these questions, I think that one cannot

dispense with addressing not only what Nietzsche wrote during that summer in

Sils-Maria, but also what he was reading before and after the famous first

sketch of the eternal return. One needed to move from the Goethe-Schiller

Archive, where Nietzsche's manuscripts are kept, to the Duchess Anna Amalia

Library of Weimar, where Nietzsche's personal library is kept, so as to

retrieve the volumes that made up, in the summer of 1881, the portable library

of this wandering philosopher. Reading these volumes all at once, while letting

myself be guided by Nietzsche's hand-written annotations in the margins allowed

me to appreciate that I was finding myself facing a larger debate which one

needed to reconstitute and whose arguments and protagonists Nietzsche knew very

well.

After the discovery of the two principles of thermodynamics

began a debate about the dissipation of energy and the thermal death of the

universe which framed the modern renewal of the debate between the linear and

circular conceptions of time.[31] Scientists such as Thomson, Helmholtz, Clausius, Boltzmann and-by way of Kant,

Hegel and Schopenhauer-philosophers such as Dühring, Hartmann, Engels, Wundt

and Nietzsche have tried to address this problem by using the force of

scientific argumentation and of philosophical discussion. Whoever believed in

an origin and a final end to the motion of the universe (be it in the physical

form of the gradual loss of heat, or in the metaphysical form of a final state

of the "world process"), relied on the second principle of thermodynamics or on

the demonstration of the thesis of Kant's first cosmological antinomy. On the

contrary, those who refused to admit a final state to the universe used

Schopenhauer's argument of infinity a parte ante-according to which if a

final state were possible, it should already have established itself in the

infinity of time past-to propose henceforth a number of alternative solutions.

Scientists would propose the hypothesis that energy could have re-concentrated

after a cosmic conflagration, thus reversing the tendency towards dissipation.

Those belonging to the monistic and materialistic tradition relied on the first

principle of thermodynamics and on the infinity of matter, space and time, and

regarded the universe as an eternal succession of new forms. A certain critical

agnosticism was widespread among scientists and philosophers, oftentimes

through a reaffirmation of the validity of Kant's antonymic conflict, this

movement avoided to take a stand on specifically speculative issues. Other

German philosophers, like Otto Caspari, or Johann Carl Friedrich Zöllner, had

reintroduced an organicist and pan-psychical conception of the universe,

investing atoms with the ability to escape any state of balance. Indeed, it is

probably one of Otto Caspari's works, The Correlation of Things (Der

Zusammenhang der Dinge. Gesammelte philosophische Aufsätze (Bleslau:

Trewendt, 1881)), which awakened Nietzsche's interest for all things

cosmological, in that summer of 1881, in Sils-Maria..

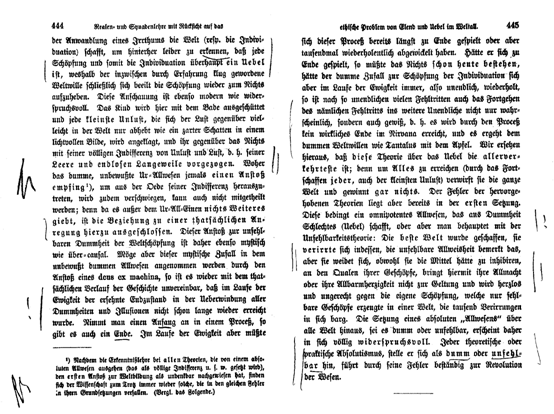

Figure 2: Otto

Caspari, Der Zusammenhang der Dinge,

pp. 444-445. Weimar, Herzogin Anna Amalia

Bibliothek, C 243.

Nietzsche's copy of the book shows a great amount of

underlining, especially in a passage from the chapter entitled "The Problem of

Evil in Reference to Pessimism and to the Doctrine of Infallibility", of pages

444-445. Addressing Schopenhauer and Eduard von Hartmann's mystical pessimism

according to which the world is the creation of a stupid and blind essence

(which, after having created the world by mistake, comes to the realization

that it had made a mistake and strives to return it to nothingness) Caspari

stresses that it is nothing short of mystical to imagine that the world may

have been borne out of a an originary and undifferentiated state. Where would

it have drawn the first impulse? But, continues Caspari, even if the world had

received this first impulse from some deus ex machina, there is no doubt

that, in the temporal infinity of past time thus far, it would have either

attained the end of the process (but this is impossible because the world would

then have ended), or it would be necessarily bound to repeat indefinitely this

original mistake, and the entire process that accompanies it. But then, what is

the process of the world? We must now take one more step back and understand

further the process of the world according to von Hartmann.

3.2 Eduard von Hartmann: Avoiding the Repetition

Eduard von Hartmann's Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869),[32] offered a philosophical system based upon the minute description of a

destructive world process, directed towards a final state. In Hartmann's view,

the "unconscious" is a unique metaphysical substance made of the combination of

a logical principle, the idea, and an illogical principle, the will. Before the

beginning of the process of the world, pure will and the idea remained in an

a-temporal eternity, free of willing or not willing to actualize itself. The

will then decided, without any rational basis, to will. It then engendered an

"empty will," full of volitional intention but deprived of any content

(Hartmann calls this the "moment of the initiative"), and finally, when the

empty will managed to unite with the idea, the process of the world commenced.

Ever since, the idea does nothing else than strive to

correct the unfortunate and illogical act of the will. By way of the

development of consciousness, it allowed human beings to understand the

impossibility of reaching happiness in the sense of the full flourishing of the

will to live. The history of the world therefore passed through the three

stages of illusion until, having reached a senile state, it finally recognizes

the vanity of all illusion and desires only rest, dreamless sleep and the

absence of pain as the best possible happiness (Eduard von Hartmann, Philosophie

des Unbewussten. Versuch einer Weltanschauung (Berlin, Carl Duncker's

Verlag, 1869): 626).

At this stage, the idea, in its cunning, has accomplished

its task: it created a quantum of "will to nothingness" which suffices to

annihilate the will to live. The moment in which the collective decision will

lead to the destruction of the whole universe is imminent and, when this grand

day comes, the will shall return to the bosom of the "pure power in itself," it

will be, once again, "what it was before any volition, that is to say, a

will that can will and not will" (Hartmann (1869): 662). Hartmann hopes, of

course, that at this point, the unconscious will have lost all will to produce

that vale of tears again and to recommence again the senseless process of the

world.

On the contrary, interpreting Schopenhauer's concept of will

as a "not being able to not will," as an eternal willing creating an infinite

process in the past and in the future, would lead one to despair, because this

would suppress the possibility of a liberation from the senseless impulse of

the will. But fortunately, says Hartmann, while it is logically possible to

admit the infinity of the future, it would be contradictory to regard the world

as deprived of a beginning and extending infinitely in the past. Indeed, if

this were case, the present moment would be the completion of an infinity,

which Hartmann explains in the third edition of his work, is contradictory. It

is remarkable that in this "demonstration," Hartmann introduces (without

mentioning his source and more importantly without stressing their antinomic

context) the arguments used by Kant in his demonstration of the first

cosmological antinomy. Kant's demonstration goes as follows:

Thesis: 'The world has a beginning in time, and in space it is also enclosed in boundaries.' Proof: 'For if one assumes that the world has no beginning in time, then up to every given moment in time an eternity is elapsed, and hence an infinite series of states of things in the world, each following another, has passed away. But now the infinity of a series consists precisely in the fact that it can never be completed through a successive synthesis. Therefore an infinitely elapsed world-series is impossible, so a beginning of the world is a necessary condition of its existence, which was the first point to be proved (Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, tr. by R. Guyer and A. W. Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998): B 454, p. 470).

Hartmann knows Schopenhauer's critique of Kant's argument, which demonstrates that it is in fact possible and not contradictory to develop an infinity in the past from the present and that it is therefore not logically necessary to postulate a beginning of the world:

The sophism consists in this, that, instead of the beginninglessness of the series of conditions or states, which was primarily the question, the endlessness (infinity) of the series is suddenly substituted. It is now proved, what no one doubts, that completeness logically contradicts this endlessness, and yet every present is the end of a past. But the end of a beginningless series can always be thought without detracting from its beginninglessness, just as conversely the beginning of an endless series can also be thought. (Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, tr. by E.F. Payne (1969): II, 494)

However, Hartmann objects that the regressive movement

postulated by Schopenhauer is possible only in thought: it remains nothing more

than an "ideal postulate" with no real object and which "does not teach us

anything about the real process of the world that unfolds in a movement

contrary to this backwards movement of thought" (Hartmann, Philosophie des

Unbewussten, third edition (1871): 772). Hartmann affirms that if

unlike Schopenhauer one admits the reality of time and of the world process,

one must also admit that the process must be limited in the past and therefore

that there must be an absolute beginning. In Hartmann's mind, failure to do so

would result in positing the contradictory concept of an accomplished infinity:

"The infinity that from the point of view of regressive thinking, remains an

ideal postulate, which no reality may correspond to, must, for the world, whose

process is, on the contrary, a progressive movement, open up to a determinate

result; and here the contradiction comes to light" (Hartmann (1871): 772).

What really "comes to light" in this passage is the fact that Hartmann does not

provide a demonstration but a petitio principii. Indeed, the concept of

the world process analytically contains the concept of a beginning of the

world. In all rigor, it is therefore impossible to demonstrate these concepts

with reference to each other. Secondly, Hartmann's view that one is bound to

accept the reality of the world process even if one rejects the ideality of

Schopenhauer's time is mistaken. Hartmann believes that if time is real there

must be a world process with both an absolute beginning and an absolute end.

Without any justification, Hartmann jumps from Schopenhauer's negated time to

oriented time.

With regard to the end of the world, Hartmann commits to the

same fallacy because he uses the idea of progress to demonstrate the end of the

world and ... vice versa. As a result, our philosopher absent-mindedly stumbles

out of demonstration into mere postulation again: "If the idea of progress is

incompatible with the affirmation of an infinite duration of the world

stretching back into the past, and since in this past infinity, all the

imaginable progress may have already happened (which is contrary to the idea of

actual progress itself) we cannot assign an infinite duration into the future

either. In both cases, one suppresses the very idea of progress towards a

pre-determinate goal; and the process of the world resembles the labor of the

Danaids." (Hartmann (1869): 637) Nietzsche quotes this passage as early as the Untimely

Meditation on history (1874), and takes a stab at exposing the admirable

dialectics of this "Scoundrel of all scoundrels," whose consistent arguments

illustrate the absurdities intrinsic in any teleology.[33]

Hartmann's view is that the world process leads into a final

state absolutely identical to the initial state. However, it follows from this

that even as the cosmic adventures of the unconscious come to a close, we are

still haunted by the specter of a new will and of another beginning of the

world process. This exposes a serious internal flaw of Hartmann's system

insofar as it jeopardizes the possibility of a final liberation from existence

and suffering. This is why in the last pages of his work, "On the Last

Principles," he painstakingly calculates the degree of probability of a

reawakening of the volitional faculty of the unconscious. Insofar as the will

is entirely free, unconditioned and a-temporal, the possibility of a new

volition is left to pure mathematical chance and is therefore ½. Hartmann

further stresses that if the will were embedded in time, the probability of the

repetition would amount to 1 and the process of the world would be bound to begin again, in an eternal return which would completely preclude the

possibility of a final liberation. Fortunately, this is not the case

since-according to Hartmann's remarkable logic-the world-process develops

through time, but the original will is outside of time. In fact, one may even affirm,

along the lines of Hartmann's peculiar theory of probability, that every new

beginning gradually reduces the probability of the next beginning: let n be the number of times that the will is realized, the probability of any new

realization is ½ n. "But it is clear that the probability ½ n diminishes as n increases, in a way that suffices to reassure us in

practice" (Hartmann (1869): 663).

3.3 Dühring and Caspari: Necessity and Rejection of the Repetition

We can now better understand the meaning of the polemic between Caspari and Hartmann contained in the pages 444-445 of Der Zusammenhang der Dinge, which I have mentioned above. There, Caspari took over the argument of the infinity a parte ante in order to claim that if a final state were possible, it should have already been reached in the infinity already past and all motion would therefore have come to a stop. Yet, such hasn't been the case, since the world is still in motion. Indeed, far from diminishing with every repetition, the probability of a new beginning is always equal to 1 and this will necessarily produce the repetition of the same process. Thus Hartmann's world process moves a circle instead of evolving towards one goal. But for Caspari this infinite circular movement represents the greatest ethical perversion and amounts in and of itself to a definitive refutation of the whole of Hartmann's philosophy. Here is a translation of the central passage of these two pages of Caspari's:

Assuming that it be possible, by way of some deus ex machina, to suppose that this mystical event indeed existed at the heart of the stupid and unconscious essence of the world. It remains that this event would be incompatible with the effective unfolding of history and that in the course of eternity the highly desired final state where all stupidities and illusions are overcome has already occurred a long time ago. If one makes the hypothesis that in a process there is a beginning, then there also has to be an end. Consequently, in the course of eternity, this process must have already unfolded a long time ago or else it was repeated a thousand of times. If it had unfolded until the end, then nothing should be here today. If, on the contrary the stupid chance which engendered the creation of individuation repeated itself forever, that is to say to the infinite in the course of eternity, then, the continuation, after an infinite number of missteps, of the same missteps in the infinite future, is not only probable but assured. That is to say that through the process, one would not attain any true end in Nirvana, and that the stupid will of the world would be victim of the same thing as Tantalus with his apple. This demonstrates that this theory relative to evil in the world is the most absurd, since in order to posses everything (through the elimination of all suffering, down to the smallest), it rejects the whole universe and gains absolutely nothing (Caspari, Der Zusammenhang der Dinge (1881): 444-445).

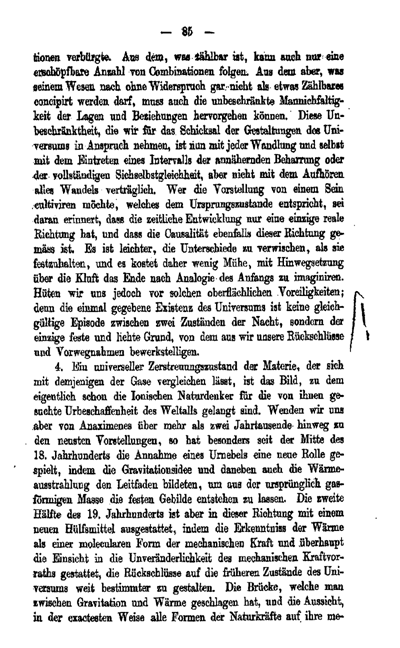

Here, Caspari enters the polemic that opposed Eugen Dühring and Eduard von Hartmann, the most famous German philosophers of the time, with regard to the possibility of a new beginning of the world-process, after the final state.[34] In the "schematism of the world," a section of his Cursus der Philosophie, Eugen Dühring rejected the infinity of space and the regressive infinity of time, and he maintained only the possibility of the infinity of future times (Dühring, Cursus der Philosophie als streng wissenschaftlicher Weltanschauung und Lebengestaltung (Leipzig: Koschny, 1875): 82-83). However, once he had outlined the "real image of the universe", he had interrupted the construction of his system in order to sketch out the false image of the universe, which arises when "unreflective imagination projects an eternal play of mutations into the regressive infinity of time. It would seem possible that, just as we went from the originary undifferentiated state of movement and matter, one could, in the future, return to a state identical to the original state and-Dühring suggests, in an allusion to Hartmann-"there would even be a way of thinking, for which this coordination between the beginning and the end may appear greatly attractive" (Dühring (1875): 83). But if the world-process leads into a state identical to the original state, Dühring continues, Hartmann's probabilistic calculus is powerless to avoid any new beginning and the "absolute necessities of the real" warrant that an infinite repetition of the same forms must necessarily occur.[35] At this point, Dühring introduces an ethical objection, namely that this "gigantic extension of the temporal interval" would indeed lead mankind to a state of general indifference towards the future, and would sterilize its vital impulses: "it is obvious that the principles that make life attractive do not accord with the repetition of the same forms." (Dühring (1875): 84) Dühring therefore rejects Hartmann's philosophical system because it leads into an anti-vital view of the world that is, into a desolate repetition of the same during an infinite future. For Dühring, like for Caspari later, the eternal return of the same is the ethically undesirable consequence that makes Hartmann's philosophy altogether wrong, trivial and absurd. Dühring brings his charge to a close with a severe warning:

Let us beware [Hüten wir uns], in any case, from such futile absurdities; because the existence of the universe, given once and for all, is not an indifferent episode between two nocturnal states, but the only solid and shining foundation upon which we could apply our deductions and previsions (Dühring (1875): 85).

On July 7th 1881,[36] Nietzsche had received in Sils-Maria Dühring's Course of Philosophy, which his sister had sent him. In his copy, he drew a line and an exclamation mark in the passage where Dühring warned us against the eternal return: hüten wir uns. The parody is in the making...

Figure 3: Eugen Dühring, Cursus der Philosophie, p.85. Weimar, Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, C 255.

3.4 The Ass-Talk of Biological Atoms

Before we return to Nietzsche, it is worth recalling Otto

Caspari's intention: he used the argument of the infinity a

parte ante, in order to oppose another range of claims-scientific more than

philosophical-which predicted the end of the world by thermal death. In 1874,

he had published a pamphlet entitled Thomson's Hypothesis of a Final State

of Thermal Balance in the Universe Considered from a Philosophical Point of

View, in which he attacked the mechanistic and materialistic cosmologies of

the time and opposed it with an organic and teleological vision of the totality

of natural phenomena. In this pamphlet, Caspari described the universe not as a

physical mechanism but as a great living organism or a "community of ethical

parts." Since the dividing line between organic and inorganic had been

abolished in principle by the recent discoveries of biology, Caspari tried to

move from a vision of the organic as a machine to a vision of the cosmos as an

organism. He therefore used the objections put forward by Robert Mayer,

Friedrich Mohr and Carl Gustav Reuschle against Thomson, Helmholtz and

Clausius, and above all he recalled the polemic of Leibniz against Descartes as

a way to simplify and reduce the ongoing debate to his own view.

In his famous work entitled On the Conservation of Force (1847), Hermann von Helmholtz had divided the totality of the energy in the

universe between potential energy and kinetic energy and affirmed the

reciprocal convertibility of the two. In 1852, William Thomson pointed out that

there exists a sub-ensemble within kinetic energy, heat, which, once it has

been generated, is no longer entirely convertible into potential energy-or into

any other form of kinetic energy. Considering that the (partial) reconversion

of heat into labor is possible only in situations that present a disparity in

temperature, and that heat tends to pass from warmer to cooler bodies by

spreading on an even temperature level through space, Thomson concluded that

the universe tends towards a final state where any energetic transformations,

every movement and every form of life will cease:

We find that the end of this world as a habitation for man, or for any living creature or plant at present existing in it, is mechanically inevitable.[37]

Caspari used the argument of the infinity a parte ante to oppose the prediction involved by Thomson's mechanism: "it is not difficult to show that the universe, which has existed in all eternity, would have already come to a state of total equilibrium of all its parts" (Caspari, Die Thomson'sche Hypothese von der endlichen Temperaturausgleichung im Weltall, beleuchtet vom philosophischen Gesichtspunkte (Stuttgart: Horster, 1874): IV). Hence, if every mechanism reaches a state of equilibrium and if the universe has not yet reached it in the infinity of past time, it follows that the universe cannot be considered to be a mechanism, but a community of parts whose movements do not abide to a mechanical law but to an ethical imperative. Caspari's atoms (which bring to mind those in Leibniz's Monadology) resemble some sort of biological monads, endowed with internal states. For Caspari, every atom obeys the ethical imperative to participate in the conservation of the general organism and its movement does not only follow the simple physical kind of interaction but also an a priori law ensuring that thermal equilibrium, which is the unavoidable result of all purely mechanical interaction, is avoided:

In order to resolve the difficulties mentioned earlier, we must return to Leibniz at least with regard to the possibility to conceive of atoms as biological atoms, that is to say, as a sort of monad, which on the one hand are obviously subject to real physical interactions, and on the other obey the law of internal atomic self-conservation. This law compels them to follow certain directions of the movement thereby preventing the formation of those tendencies of movement which, because of their unlimited growth, would lead the whole universe (considered purely mechanically), to a state of complete equilibrium of all its parts; a state to which the whole universe, once the ability to conserve motion has been exhausted in every one of its parts, would be condemned to forever (Caspari, Die Thomson'sche Hypothese (1874): V).

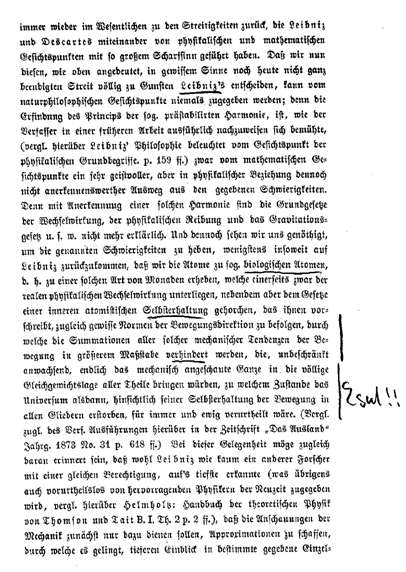

herefore, the universe is not a watch in need of rewinding or some steam engine on the verge of a fuel failure. On the contrary, it is, says Caspari after Leibniz: "A watch that rewinds itself, comparable to the organism that seeks its own nourishment [...]. The universe is not in itself a pure, dead, mechanism. Leibniz, against Descartes exclaimed: 'No!' the universe is entirely made up of an independent force, which it does not draw from without" (Caspari, Die Thomson'sche Hypothese (1874): 8-9). In Nietzsche's copy, this last sentence received merely a marginal mark, but the last part of the preceding quotation is graced with a big "Esel" ("Ass") followed with two exclamation marks.

Figure 4 : Otto Caspari, Die Thomson'sche Hypothese (1874): V, Weimar, Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, C 379.

Indeed, after having read Caspari's first book, The

Correlation of Things, Nietzsche went on to read his pamphlet against

Thomson's hypothesis, as well as a series of studies, which he found discussed

in The Correlation of Things. Nietzsche's writings and his readings

indicate that, even before 1881, his level of awareness of cosmological

problems was fairly broad.[38] However, it is during the summer of 1881, at the time when his idea of the

eternal return "surges over the horizon," that Nietzsche devotes himself more

intensively to these types of readings. In my opinion, the main source of these

new reflections is precisely Caspari's The Correlation of Things, which

Nietzsche's editor delivered to him in St Moritz (see the letter to Schmeitzner

of June 21st 1881). Caspari's chapter entitled "The Contemporary

Philosophy of Nature and its Orientations," which is a study of Gustav Vogt and

Alfons Bilharz's philosophy of nature, gave Nietzsche access to a presentation

of the current state of cosmological debates as well as some bibliographical

references. Further, in his letter to Overbeck of 20-21st August

1881, Nietzsche begged his friend to send him the following works, which he

found mentioned in Caspari.

I would like to ask

you to buy me a few volumes in bookstores:

1. O. Liebmann, The Analysis of Reality [quoted by Caspari

(1881) on pp. 215 and 223].

2. O. Caspari, The Hypothesis of Thomson (Stuttgart:

Hörster, 1874) [quoted by Caspari on pp. 33 and 51].

3. A. Fick, "Cause and Effect" [Quoted by

Caspari, in quotation marks, on p. 39 and as a "memorable work," on p. 51].

4. J. G. Vogt, Force, Leipzig,

Haupt and Tischler 1878 [quoted by Caspari on pp. 28-29, discussed at length on

pp. 41-48].

Liebmann,

Kant and his Epigones [Quoted by

Caspari on p. 58]. [.]

Does the Zurich

reader's association (or the library) hold the "Philosophischen monatshefte"? I

would need volume 9 from year 1873 [quoted by Caspari on pp. 80, 82 and 93] and

also of year 1875 [quoted by Caspari in the same way, without volume number, on

pp. 128 and 134]. Then the review Kosmos, volume I [quoted by Caspari on pp. 36, 51, 146, 180, 182,

and 378].

Is there a complete

edition of the Discourses by Dubois-Reymond? [quoted

by Caspari on pp. 20, 420 and 486].

Nietzsche also

requested Afrikan Spir's book, Thought

and Reality, which he was used to

re-reading periodically when dealing with speculative questions.[39] As soon as he received these books, he

immersed himself in the reading of Caspari's pamphlet against Thomson and his

first reaction, as we saw, was to call Caspari's hypothesis of biological

monads supposedly able to warrant the conservation of movement "ass-talk." One

encounters this reaction again in the margin to Caspari's writing, which is

accompanied with a fragment from Notebook M III 1 ("The most profound

mistake possible is to affirm that the universe is an organism. [.] How? The

inorganic would be the development and the decadence of the organic!?

Ass-talk!!"), which is followed by

another fragment in all likelihood aimed at Caspari: "Absolute equilibrium is either in and of itself impossible,

or the modifications of force enter

into the cycle before any equilibrium, in itself possible, is reached.

-Attributing to being the 'instinct of self-preservation'! Madness! And attributing to the atoms 'the striving towards pleasure and

displeasure'!"[40]

On August 26th, Nietzsche wrote a new plan for a

book on the eternal return in M III 1 entitled "Noon and Eternity"

(PF 11 [195]). Nietzsche takes over his cosmological reflexions in the very

next fragments. There, he pursues his constant dialogue with Caspari and

develops a harsh critique of his organicism. Caspari pointed out that

Democritus' atomistic theory-which, in Dante's formulation, "sets the world on

chance"-is either a hidden teleology or a theory contradicted by the experience

(Caspari, Der Zusammenhang der Dinge (1881): 124). Indeed, Caspari

contends that a world governed by chance, which had succeeded in avoiding the

state of maximum equilibrium so far, could not be called totally blind; on the

contrary it must have been directed by some form of teleology. If conversely no

teleological principle were guiding it, then it should already have

reached this state of maximum equilibrium and of motionlessness. In this case,

however, the world would still be motionless, and experience demonstrates that

the opposite is the case.

Nietzsche refers to these arguments in the posthumous

fragment 11[201] when he writes that organicism is a "hidden polytheism," and a

modern shadow of God. There, he directs the objection of infinity a parte ante against Caspari: if the cosmos could have become an organism, it would have

done so by now.

In the modern scientific realm, what corresponds most to the belief in God is the belief in the whole as an organism: this disgusts me. Turning what is absolutely rare, unspeakably derivated, the organic, which we perceive only on the crust of the earth into the essential, the universal, the eternal! This is humanization of nature all over again! And the monads, which, taken together, would form the organism of the universe are nothing but hidden polytheism! Endowed with foresight! Monads, which would be able to prevent certain possible mechanical results such as the balance of forces! This is phantasmagorical! If the universe could ever become an organism, it would already have become one.

But, Caspari insists, what then is it that has been preventing the attainment of a state of equilibrium so far (and will always prevent, since a temporal infinity has already unfolded by now) if not the intentionality of atoms? If in infinity "all the possible combinations must have taken place, it follows that even the combination that corresponds to the state of equilibrium must have taken place and this contradicts the facts of experience" (Caspari (1881): 136). In his copy of the book, Nietzsche traced two lines on the side of this sentence, and he specifically addresses this objection in fragment 11 [245] of 1881. There, he draws a distinction between the configurations of force that are merely possible and those that are real. For him, the balance of forces-that is to say, thermal death-is one of the possible cases, but since it has never been and never will be attained, it is not a real case.

If a balance of forces had been attained at any moment, this moment would still be going on: therefore, it never happened. The present state contradicts this proposition. Supposing that a certain state rigorously identical with the present state had, one day, existed, this supposition is not refuted by the present state. As one of the infinite possibilities, it is necessary that the present state had been given anyway, since until now an infinite period of time has already unfolded. If equilibrium were possible, it must have occurred; and if the present state has already taken place, then so too the one that preceded it as well as the one preceding that one. Therefore it has already taken place a second time, a third time and so on. And likewise it shall take place again a second time, a third time. Innumerable times forwards and backwards. This amounts to saying that all becoming occurs within a repetition of an innumerable number of absolutely identical states. [.] The immovability of forces, their equilibrium is a conceivable case, but it has not occurred. As a result the number of possibilities is greater than the number of realities. -The fact that nothing identical recurs may be explained not thanks to chance, but only thanks to an intention infiltrated within the essence of force. Indeed, supposing an enormous amount of cases, the random occurrence of the same combination is more probable than the same combination never recurring.

Now we can go back to the page that follows the first sketch of the eternal return, which triggered our analysis. As we remember, it began with the warning: "Let you beware (Hütet euch zu sagen) that the world is a living being." Things have now become clearer: Hüten wir uns is the phrase which Eugen Dühring uses at the end of his refutation of Eduard von Hartmann's system of the world, a system which he regarded as anti-vitalistic because it led logically to the repetition of the identical. Dühring wrote: "Let us beware from such futile absurdities." Organicism is Otto von Caspari's answer to the problem of the dissipation of energy, of the thermal death of the universe and of all sorts of teleologies. Against Dühring, against Hartmann, but also against the extension of the second principle of thermodynamics to the universe, Caspari contends that the world will never be able to attain the final state because it is made up of some sort of biological atoms. Nietzsche supports Caspari in his critique of teleology, and the arguments he uses against the final state of the universe coincide with Caspari's. However, he still regards organicism as the worst form of anthropomorphism, a hidden polytheism and rejects it with all his might. Nietzsche uses a parody of Dühring's phrase "Hüten wir uns" ("Let us beware") in order to ridicule and refute at the same time Caspari's organicism, Thomson's mechanism, Hartmann and Dühring's world process and other false interpretations of the universe. He also uses this debate to develop his arguments in favor of his idea of the eternal return of the same. A reading of some of the other fragments from Notebook M III 1 confirms that this is not a matter of chance but a subtle intellectual game. Nietzsche writes:

Let us beware [hüten wir uns] to assign an aspiration, a goal of any kind to this cyclical motion, or to regard it according

to our needs as boring, stupid, etc.

Undoubtedly, the supreme degree of unreason manifests itself within it just as

much as the contrary: but we could not judge it according to this fact, neither the reasonable nor the unreasonable are predicates that

could be attributed to the universe. -Let us beware [hüten wir uns] from regarding the law of this circle as having become,

according to the false analogy of the cyclical movements taking place within the ring: there has not been

first some chaos and then progressively a more harmonious movement, and finally

a stable circular movement of all forces. On the contrary, everything is

eternal, has not come once into existence. If there had been chaos of forces,

the chaos itself used to be eternal and recurred in every circle. The circular

course has no resemblance with what has

become, it is the original law just as well as the quantum of force is the original law, without exception or